The Liberty Tree and the Expansion of Political Protest

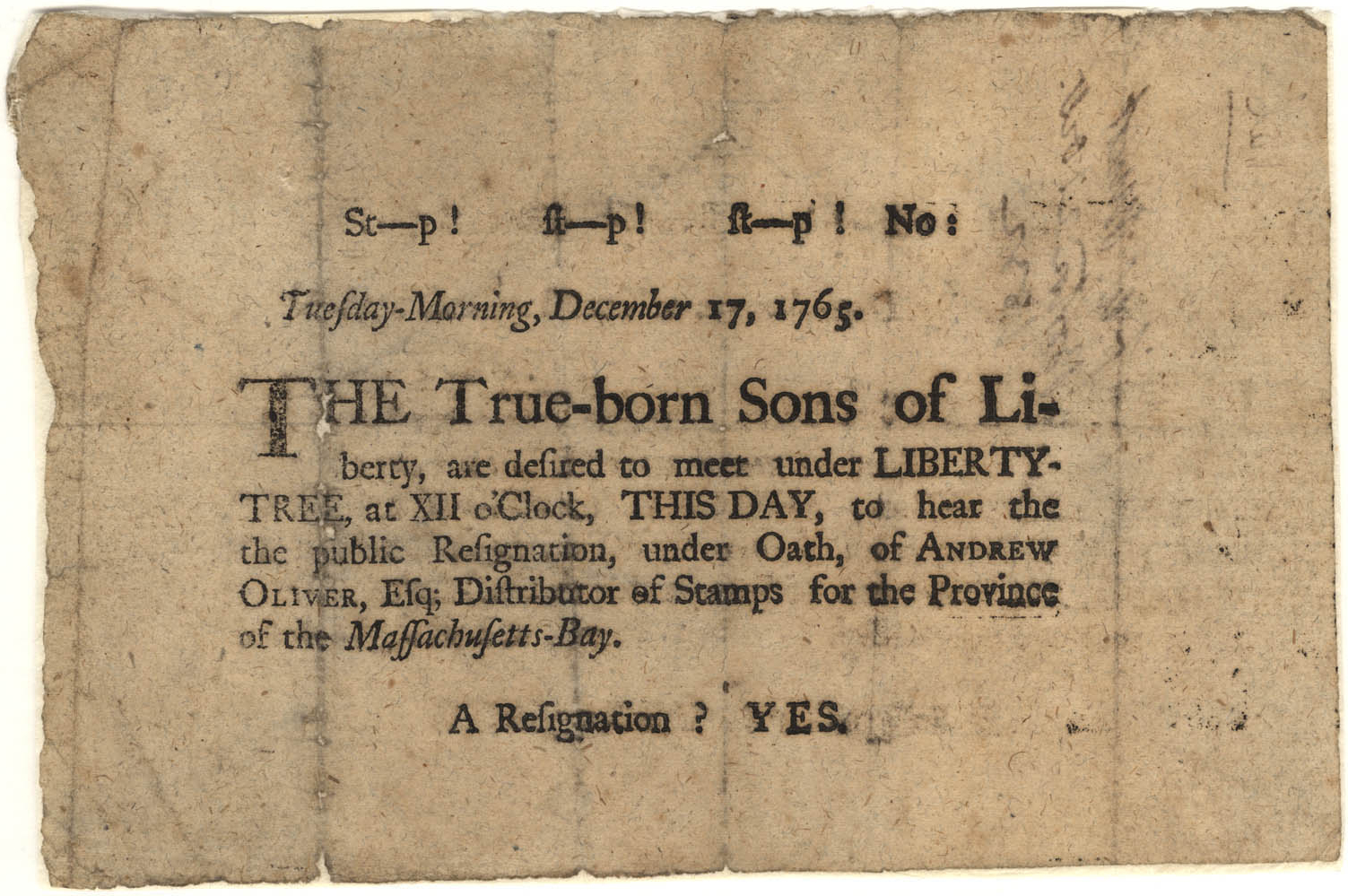

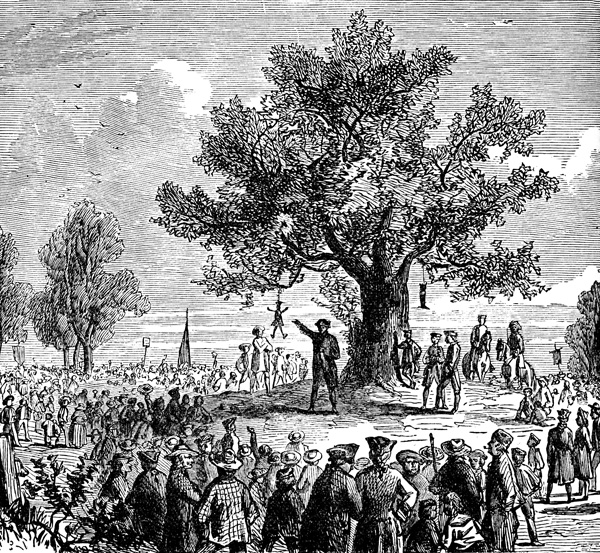

On August 14, 1765, the a group of Boston activists opposing the Stamp Act hung effigies from the largest and most magnificent elm tree in Boston. The effigies were of Lord Bute, the former prime minister held responsible for the hated tax; Andrew Oliver, the Boston merchant designated as the local stamp distributor; and the Devil. The display drew thousands of residents (out of a population of about 16,000) and served the important goal of democratizing protest, enlarging the public sphere of political participation well beyond those who could read and understand the colonial pamphleteers who argued from English constitutional law.

From Revolutionary Dissent, Chapter 4:

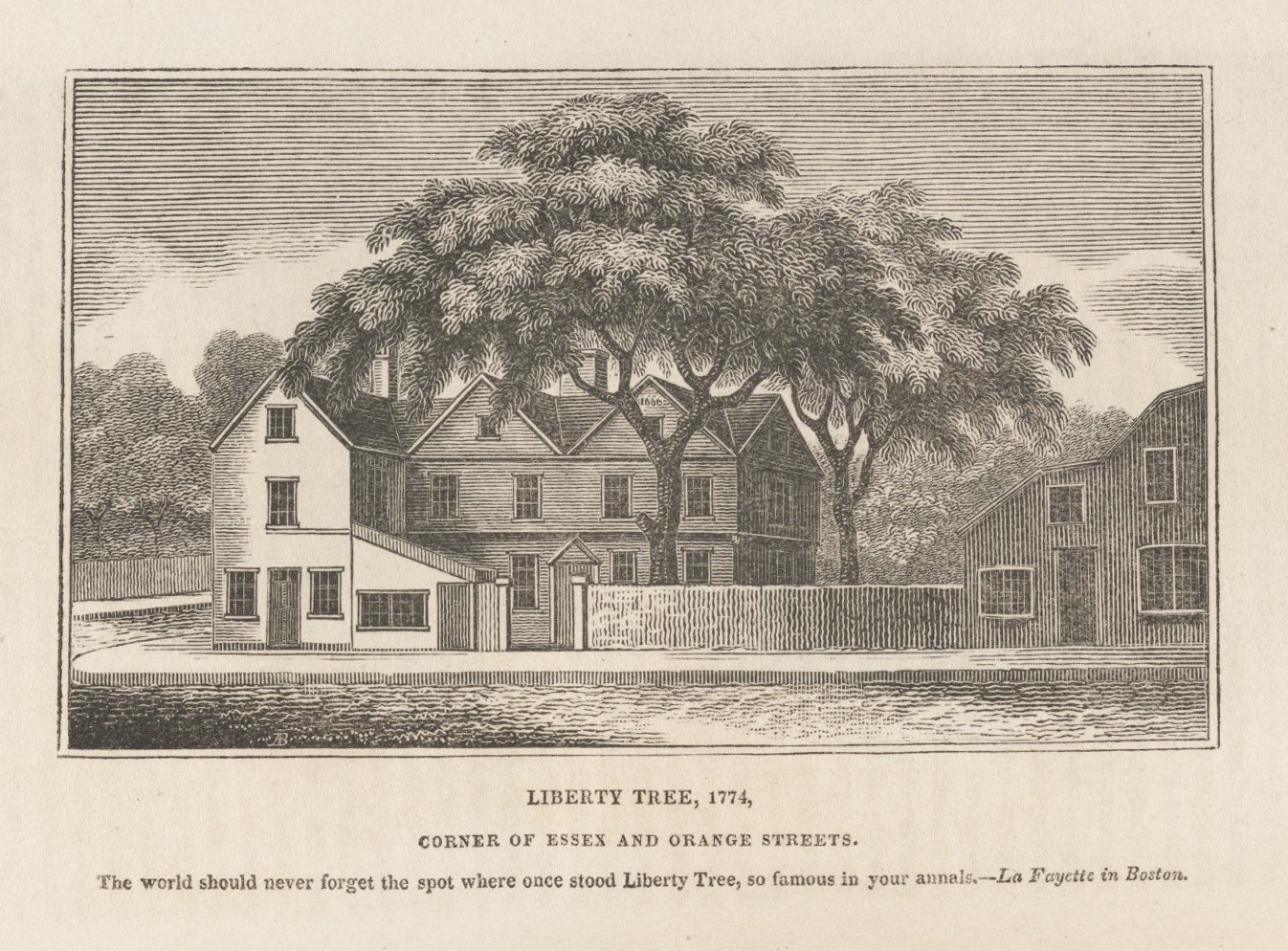

For the colonists, though, the elm in front of Deacon Elliott’s house became a symbol...of freedom and of opposition to arbitrary authority. It would unite patriots for the next decade…[T]he Liberty Tree became an inspiring image—so majestic and so ancient, reaching for the heavens in defiance of the arbitrary forces of nature. If the power of the King and Parliament counted as only slightly less than a force of nature, the Liberty Tree fortified the patriots’ resolve to oppose it when necessary. It became it an important venue for political assembly, an open-air marketplace of ideas. It served as Liberty Hall, an outdoor meeting space to discuss colonial grievances and stage protests against the actions of royal authorities in the decade to come.

Dedication of the Liberty Tree and its role as centerpiece of the gathering on August 14 showed how the universe of political expression was expanding. The tree, the boot, and the effigies expressed ideas in ways very different from the essays and letters and petitions that had dominated the debate until then. Unlike other forms of expression that involved words, either spoken or printed, the tree and the effigies were symbols. But they were speech nonetheless...

Symbolic speech, in fact, possessed some power that the written and spoken word did not. The essays and speeches against the Stamp Act used complex arguments that were foreign to many people’s understanding and experience, and even vigorous opponents of the tax sometimes disagreed among themselves on many of the arguments they were putting forward. But symbols stripped away the complexity of intellectual arguments and offered immediate clarity. For the people of Boston and elsewhere, Liberty Trees and effigies of stamp distributors stood for one big idea—the right to be free of arbitrary power, exercised in a legislative body far away without participation of the colonists’ own representatives.